– Jeanne M. Slattery and Melissa K. Downes

Jeanne Slattery and Melissa Downes

We live in a world that is trying to reduce education to a false equation and, in the process, is devaluing the importance of and commitment to a quality education. We believe our culture is less respectful of education than at any other point in our lifetimes.

As we consider the narrative that is being spun about education, we see at least ten myths, four of which we will consider this week, the balance in a future issue. We think these myths are pernicious and damaging – to our universities, our students, our communities, and our nation. Naming and exploring these myths would seem to be an important first set of steps to dispelling them.

Myth 1: Colleges are businesses and should be run that way.

Colleges and universities have a complex infrastructure; sell services to consumers; both bring in and spend money; and have income goals that depend, in part, on a strong corporate brand (Courageous, Confident, Clarion). Universities can be state-owned, but can also be privately owned; and can be either not for profit or for-profit in their set up (Limburg, 2013). Yes, colleges are businesses; however, they are also much more.

That colleges are businesses does not mean that they should be run as traditional businesses, focusing on money first and foremost. Kasperkevic (2014) argued:

The competition among these institutions of higher learning has had an adverse effect on those they are supposed to serve. From less rigorous curriculums to higher tuition prices, the universities have changed the way Americans think of educations. Students are now consumers and university presidents are CEOs overseeing multiplexes of the college experience. (para. 7)

The kind of changes that many colleges and universities have made in order to attract more students may work in the short term, but they tend to weaken the brand and the quality of education for our students in the long run.

Beyond this, some part of what a college education needs to do—promote critical thinking; help develop a stronger, more professional work ethic; enhance attitudes, behaviors, and knowledge that will help students engage with the world in thoughtful, complex, and creative ways—is not always comfortable or easy. Hard work, risk-taking, and reassessing one’s beliefs and values won’t necessarily “sell a college.” But to ignore or remove these necessary components of a college education damages our communities (big and small), our businesses, and our culture. It is to sell out.

A healthy school maintains both a good bottom line and a strong vision of what it wants to be. It puts students and their educations first and the bottom line an important second. We believe that putting our students first and committing to the core values of higher education will actually make our schools healthier and more financially viable.

Myth 2: Increases in college costs are due to the rising cost of faculty.

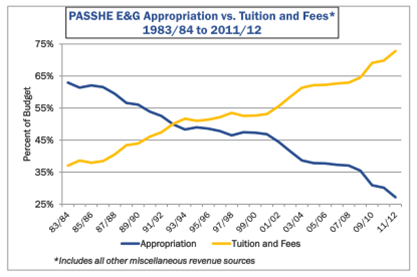

Figure 1. Changes in funding of Pennsylvania state universities across a 30 year period (Mahoney, 2014)

The cost of college has shifted from state funding to individual students (tuition and fees) over the last 30 years. In 1984 in Pennsylvania, students paid about 35% of the costs of their education, while they paid almost 75% in 2012 (Mahoney, 2014). See Figure 1. While the exact numbers differ, the same pattern is seen in many other states (e.g., Hiltzik, 2016; Washington State Budget and Policy Center, 2012).

If these losses were matched by increases in student grants and scholarships, no problem. Unfortunately, they have not been. Students are being asked to bear a larger proportion of the costs of their education.

Figure 2. Percentage change in the number of employees in higher education institutions, by category of employee, 1975 and 1976 to 2011 (AAUP, 2013-2014).

Part of the increased costs in a college education, then, is due to changes in state funding. The story is more complex, though. While the faculty:student ratio has stayed relatively constant (although with more faculty in adjunct positions), the number of administrators has, in fact, more than doubled (American Association of University Professors [AAUP], 2013-2014; Ginsberg, 2011; Stenerson, Blanchard, Fassiotto, Hernandez, & Muth, 2010). See Figure 2. The number of adjuncts and full-time nonfaculty has increased precipitously (AAUP, 2013-2014).

We suspect that administrative bloat is at least in part in response to increasing government demands for paperwork. We value the work completed by administrators, but ask that they not attribute the institution’s monetary woes to us.

Myth 3: Faculty only work 17 hours a week.

Earlier this year we wrote about Chancellor Brogan’s negligent statement to Pennsylvania legislators suggesting that faculty work 17 hours/week – while he also implies some may work less (Downes & Slattery, 2016). It is hard for me to imagine that a faculty member could accomplish even the bare minimum in 30-40 hours per week. Most of us go well beyond this. In fact, it’s difficult to do our job – grading, preparing classes, research, committee work, advising students and student groups, outreach to our communities, assessment – in less than a 50-60 hour workweek.

We believe that Chancellor Brogan’s statement both reflects anti-education beliefs and contributes to our culture’s acceptance of this myth and these beliefs: Teaching is easy and requires no special expertise. Education isn’t important. We recognize the irony – the person who is supposed to be championing and strengthening education in Pennsylvania is contributing to its erosion.

We experience considerable joy from our work, but it is not easy work. It is meaningful work, but it is hard. Part of why we love teaching (and writing and research and service) is that it is important; it makes a difference.

Myth 4: States shouldn’t invest in universities, because a college education is solely an individual benefit.

Students’ educations benefit the larger community in many ways. Miller (2010) argues:

College graduates also contribute more and take less from society. During their lifetime they pay more taxes, enjoy better health, are less likely to be involved in criminal activity, and are more likely to volunteer in their communities and to vote. (para. 6)

Investing in education means investing in our society’s infrastructure. As Miller (2010) argued, investing in education means “investing in innovation, discovery, work force preparation and the growth of intellectual capital” (para. 10).

In this blog, we have focused primarily on myths about what universities are and how they should be run. These myths have important ramifications for funding for colleges and universities, the allocation of a university’s limited resources, faculty pay, and student decisions to attend college. In our next installment we will be looking more closely at the value of education for our students’ lives, their pocketbooks, and our communities.

Are there myths that you think we should consider? Leave your ideas in the Comments.

References

American Association of University Professors. (2013-2014). Losing focus: The annual report on the economic status of the profession, 2013-14. Retrieved from https://www.aaup.org/reports-publications/2013-14salarysurvey

Downes, M. K., & Slattery, J. M. (2016). Seventeen hours. Hand in Hand. Retrieved from https://handinhandclarion.wordpress.com/?s=17+hours

Ginsberg, B. (2011, September/October). Administrators ate my tuition. Washington Monthly. Retrieved from http://washingtonmonthly.com/magazine/septoct-2011/administrators-ate-my-tuition/

Hiltzik, M. (2016). When universities try to behave like businesses, education suffers. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved from http://www.latimes.com/business/hiltzik/la-fi-hiltzik-university-business-20160602-snap-story.html

Kasperkevic, J. (2014). The harsh truth: US colleges are businesses, and student loans pay the bills. Guardian. Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/money/us-money-blog/2014/oct/07/colleges-ceos-cooper-union-ivory-tower-tuition-student-loan-debt

Limburg, D. (2013). College is a business – What you should know and why. Student Choice. Retrieved from http://blog.studentchoice.org/college-business-what-you-should-know-why/

Mahoney, K. (2014). PA state senators crafting legislation to allow universities to secede from state system of higher ed. Academe Blog. Retrieved from https://academeblog.org/2014/02/24/pa-state-senators-crafting-legislation-to-allow-universities-to-secede-from-state-system-of-higher-ed/

Miller, G. L. (2010). Higher education benefits students, society. Wichita Eagle. Retrieved from http://www.kansas.com/opinion/opn-columns-blogs/article1021769.html

Stenerson, J., Blanchard, L., Fassiotto, M., Hernandez, M., & Muth, A. (2010). The role of adjuncts in the professoriate. Peer Review, 12(3). Retrieved from https://www.aacu.org/publications-research/periodicals/role-adjuncts-professoriate

Washington State Budget and Policy Center. (2012). Cuts to higher education dimming future prosperity. Retrieved from http://budgetandpolicy.org/schmudget/cuts-to-higher-education-dimming-future-prosperity

Thanks to Karen Bingham, Sean Boileau, Danielle Bryan, Iseli Krauss, Miguel Olivas-Lujan, Crystal Park, Kelly Sells, who generously shared their concerns about contemporary views of higher education.

Jeanne M. Slattery is a professor of psychology at Clarion University. She loves teaching and learning and describes herself as a learner-centered teacher. She has written two books, Counseling diverse clients: Bringing context into therapy, and Empathic counseling: Meaning, context, ethics, and skill. Trauma, meaning, and spirituality: Translating research into clinical practice will be coming out this fall. She can be contacted at jslattery@clarion.edu

Melissa K. Downes is an associate professor of English at Clarion University. She loves teaching. She is interested in talking about how people teach and enjoys sharing how she teaches. She is an 18th century specialist, an Anglophile, a cat lover, and a poet. She can be contacted at mdownes@clarion.edu

Ladies this is an important sequence of topics!

I am particularly incensed about treating schools as being in the business of satisfying clients.

You probably are aware of work that shows that hospitals that gain the highest “client (patient) satisfaction” ratings frequently rank lower in quality of care measures reflecting disease eradication or infections….

I believe the measures of client satisfaction applied to faculty and schools have similar difficulties.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think I read this in one of Gladwell’s books??? I’m not opposed to client satisfaction being ONE measure used, but we should also be looking at “quality of care” measures. Thanks for the feedback, Emily!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: 10 Myths That Damage a University. Part 2: Is College Worth It? | Hand in Hand

Directly addressing Myth # 4 is this article that will be published in the Chronicle of Higher Education in a couple of days, Jeanne, Melissa. I know you will enjoy it! http://www.chronicle.com/article/Beyond-the-College-Earnings/239013?cid=wb&utm_source=wb&utm_medium=en&elqTrackId=468ac523385541709a4c3b6229914a58&elq=4f98d2db960d4ab1a84ca8124e46646f&elqaid=12350&elqat=1&elqCampaignId=5018

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, I read it this weekend and thought it was very useful – although wish that it cited its info. Thanks much for the share!

LikeLike